In August of last year a 43-year-old woman undergoing chemotherapy treatment for nasal cancer died after receiving a massive overdose of the chemotherapy drug flourouacil. According to an Incident Report (pdf) issued by the Institute of Safe Medicine Practices Canada the dose was miscalculated by two different nurses and incorrectly programmed into an electronically-controlled pump. The woman was then sent home, where the pump poured four (4) days worth of drug into her in four (4) hours.

In August of last year a 43-year-old woman undergoing chemotherapy treatment for nasal cancer died after receiving a massive overdose of the chemotherapy drug flourouacil. According to an Incident Report (pdf) issued by the Institute of Safe Medicine Practices Canada the dose was miscalculated by two different nurses and incorrectly programmed into an electronically-controlled pump. The woman was then sent home, where the pump poured four (4) days worth of drug into her in four (4) hours.

When the woman returned to the cancer clinic to report the problem a nursing supervisor contacted the doctor on call and was told nothing could be done – there was no antidote – and the woman should be advised to call the next morning. The woman was warned of vomiting and nausea and instructed to stay hydrated.

For the next couple of days no one at the clinic paid much mind to this incident and no one advised the patient of the potential severity of consequences. On the third day someone contacted the patient and advised her to come in the next day. By the fourth day the patient was sick and returned to the clinic but there were no beds available. She was admitted the next day.

For the next two weeks this woman’s body systematically destroyed itself in a rather grotesque and painful sequence of events that led to her death in ICU approximately two weeks after her admission.

This event happened in Canada, but it could happen anywhere. It could happen in every hospital or clinic I’ve ever been in. The problem is that we rely to much on our doctors, and our nurses, to get things right and they just don’t always do so. We simply must know what they are pumping into our bodies. We must know what it is, what it does, and what the potential consequences are.

More importantly we need someone with us, and intelligent advocate, any time we undergo such a procedure because as patients we simply aren’t in any shape to think straight and ask the important questions. Someone should have noticed after an hour that the woman’s medicine was now 1/4 gone and stopped it. Someone should have known, and told the patient, that she was being poisoned (intentionally) and that an overdose would almost certainly be fatal.

My experience is that when you go into a hospital or clinic you are given a form to sign that says you could die. You get that for everything from having an ingrown toenail removed to open heart surgery. But the realistic outcomes are simply not the same for both cases. And the verbal instructions and warnings given by staff are designed to be comprehended by fifth graders and not raise anyone’s anxiety level. The result is everyone signs the form without reading it (I’m not sure it contains anything useful anyway) and, as the report shows, we rarely get the full scoop via verbal instructions or even written discharge orders.

We have made enormous improvements in healthcare over the last 50 years, but we are just nowhere near where we need to be. Until we are, we all need to educate ourselves as much as possible on what the doctors are doing to us, what the (realistic) potential consequences are, and what we should be watching for.

In August of last year a 43-year-old woman undergoing chemotherapy treatment for nasal cancer died after receiving a massive overdose of the chemotherapy drug flourouacil. According to an

In August of last year a 43-year-old woman undergoing chemotherapy treatment for nasal cancer died after receiving a massive overdose of the chemotherapy drug flourouacil. According to an  So I managed to get ahold of it and pull it out. Actually, it pretty much fell out when I touched it. And all was right with the world. Until yesterday. My eye got sore yesterday morning. By afternoon I had developed a whopping stye in exactly the same place as that in-grown eyelash. Boy, does that hurt. According to

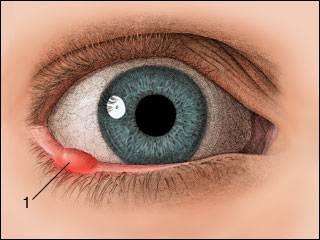

So I managed to get ahold of it and pull it out. Actually, it pretty much fell out when I touched it. And all was right with the world. Until yesterday. My eye got sore yesterday morning. By afternoon I had developed a whopping stye in exactly the same place as that in-grown eyelash. Boy, does that hurt. According to